As a follow up to my writing on Running around in the Mountains, I thought I should write a bit about my training. Physical preparation is a critical piece of the puzzle of safe travel in demanding environments, and more than that, it’s so much more enjoyable to really feel strong on adventures.

Training & Supercompensation

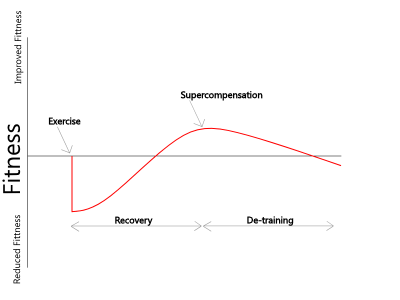

My understanding and approach to training is based on the supercomposition theory. The very high level overview of this theory is that after any given stress, the body will not only recover, but recover to a higher level of preparedness for a period after the stress. Take running for an easy example.

Say you go on a 1 mile run:

* Shortly after the run, it will be harder to run 1 mile (you’ve stressed your body’s “running system”).

* Shortly after the run, it will be harder to run 1 mile (you’ve stressed your body’s “running system”).

- A few days after going on the run, when you’ve properly recovered (with proper sleep and nutrition), it will be slightly easier to run for 1 mile.

- If you don’t run again for a while, running a mile won’t be any easier, as your fitness will return to baseline.

- If you sit on the couch for 2 months, it will be harder to run, as your body has detrained below the initial baseline.

The plot to the right shows an approximated supercompensation curve. This idea can be applied to any sort of physical (or even mental) activity: aerobic training, endurance training, strength training, power training, etc. etc.

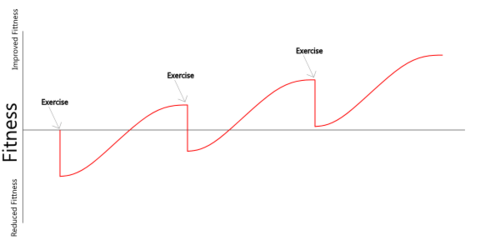

Training takes advantage of the increased period of fitness after recovery. By performing another training session during this period, supercompensation will occur again, raising one’s fitness even higher after recovery. By performing training sessions with consistency, one can raise their fitness gradually over time. Once again, this is applicable to any of the body’s physical systems. Different systems have different required stresses and periods of supercompensation; for example, tendons and ligaments take longer to recover and supercompensate compared to fast-twitch muscles, but will take much longer to detrain.

Training takes advantage of the increased period of fitness after recovery. By performing another training session during this period, supercompensation will occur again, raising one’s fitness even higher after recovery. By performing training sessions with consistency, one can raise their fitness gradually over time. Once again, this is applicable to any of the body’s physical systems. Different systems have different required stresses and periods of supercompensation; for example, tendons and ligaments take longer to recover and supercompensate compared to fast-twitch muscles, but will take much longer to detrain.

The Body’s Systems

The requirements of being a human are many, and as such there are many different systems in the body for accomplishing different types of tasks. These systems are of course closely interlinked, but in training it is useful to split them out into separate categories to focus on the ones that we cares about. Personally, I split the systems into power, strength, anaerobic endurance and aerobic endurance. They exist for me along the spectrum of time scales; aerobic endurance is the longest term system, and power is the shortest term system. More on each below:

Power

The fastest system. Think jumping, olympic lifting, sprinting short distances, speed climbing, etc. This is primarily fast twitch muscle fibers. It’s the expression of as much force as possible over the shortest period possible. Trained with plyometrics. Recruitment of fast twitch muscle fibers using carbohydrates as the fuel source.

Strength

Maximum force system. Durability. Power lifting, strongman stuff, bouldering, traditional gym workouts. Not super useful on its own, but in my own experience, one of if not the most important elements of any training program for its carryover to all of the other systems. Recruitment of all muscle fibers using carbohydrates as the fuel source.

Anaerobic Endurance

Longer term (< 30 mins) maximum force system. Extended periods of the use of force. Downhill skiing, sport climbing, mountain biking up a hill. Running a mile or a 5k as fast as you can. Anything that feels medium to really hard that you can only do for ~30 mins or less. For a lot of people, this includes hiking (think 30 mins of hard hiking, then a 10 minute rest/slow down, then another bout of hard hiking, repeated ad nauseam). Recruitment of most muscle fibers using primarily carbohydrates as the fuel source.

Aerobic Endurance

Longest term (1hr+) system for sustained activity. Half-marathon+ running, ski touring, long hiking, walking, cycling. Easy to medium effort. Recruitment of most muscle fibers using primarily fats and carbohydrates as the fuel source.

Aerobic/Anaerobic Endurance

To oversimplify, there are two different biological systems within us to provide energy: the short term system, based primary on using sugars in the absence of oxygen for energy (“anaerobic”), and the long term system, which metabolizes sugars and fats in the presence of oxygen (“aerobic”). Aerobic metabolism is much more efficient at producing energy than anaerobic metabolism. At any given point, the body is likely both of these systems at the same time to provide energy. As such, the names aerobic endurance and anaerobic endurance are a bit of a misnomer, as both metabolisms are active in both systems. I use these names instead to denote the metabolism primarily used: Anaerobic endurance is where the primary metabolism occurs in the absence of oxygen, and aerobic endurance is where the primary metabolism with oxygen.

The body can only store a limited amount of energy in carbohydrate form. This supply will be exhausted after roughly 30 minutes of hard “anaerobic” endurance on an empty stomach. I’m sure we’ve all been there- going all out for a while, feeling really good, then it gets really hard to keep going. That’s because one physically can’t; carbohydrate stores are nearly depleted, and the body is throwing up a ton of warning signals to let us know.

For longer term activity, it’s critical to develop the aerobic system. Building a stronger and more efficient aerobic system allows one to have plenty of energy for endurance activities, without having to rely on carrying around a million sugary snacks. The aerobic pathway burns carbohydrates more efficiently, and additionally taps into the fat energy stores that our body naturally carry around. Under this system, we can go for long periods without needing to eat anything at all. Even better, because the anaerobic and aerobic metabolism are separate pathways, they stack on top of each other for all activities. A stronger aerobic system not only allows for more energy during longer term activities, but adds to fitness in shorter term activities as well. Think of aerobic fitness as a “base” that anaerobic fitness sits on-top of: a strong, wide base promotes a tall peak.

Strength

I like to think of strength using an analogy of piano movers. Let’s say you have a piano moving business, and there are five pianos to move across town each day.

- If you hire one person to do it, it’s going to take them forever, and they’ll probably hurt themselves the first day.

- If you hire five people, it’s still going to take a while, and someone might still get hurt, but it will get done.

- If you hire 20 people, it’ll go quickly, and no-one is likely to get hurt.

- If you hire 100 people, it won’t be much faster than 20 people; most are going to just be standing around. It’s going to cost you a lot to pay them and feed them.

In this analogy, muscle fibers are analogous to the piano movers. If you don’t have enough for what you’re trying to do, you’re going to hurt them. Even if you have enough to get the job done, it doesn’t mean you have enough to do the job safely and efficiently. If you have too many, it’s going to cost you to feed them (caloric energy).

Somewhere in there, there’s an appropriate amount of muscle fibers/piano movers to do what you want to do well without getting hurt. It depends on what you want to do. Even if you think you have just enough to do it, you’re going to be safer and have a better time if you have more.